This year, I have been provided the opportunity to be part of a Teacher Led Inquiry Fund (TLIF) into the nature of eLearning and Personalisation. These two terms are loaded with meaning, and are easily confused. According to the TLIF application, these terms can be defined as follows:

Personalising education involves: a highly-structured approach that places the needs, interests and learning styles of students at the centre, engages learners who are informed and empowered through student voice and choice, assessment that is related to meaningful tasks and includes assessment for and by students and a focus on improving student outcomes for all and a commitment to reducing the achievement gap. This pedagogical approach is seen as an alternative to so-called “one-size-fits-all” approaches to teaching and learning.

As part of the project, we are not aiming for individualised learning and will avoid this confusion by making the distinction clear. According to Pollard and James (2004) a focus on individualised learning is likely to limit knowledge creation. What we seek is “participation in communities of learning and partnerships between teachers, parents and young people” to enable us to build a solid basis for 21st century education on the Kāpiti Coast. Personalisation leads to students collaborating on areas of interest, focus and also areas where personal learning needs have been identified.

e-learning is defined as learning and teaching that is facilitated by or supported through the appropriate use of information and communication technologies (ICTs). E-Learning can cover a spectrum of activities from supporting learning to blended learning (the combination of traditional and e-learning practices), to learning that is delivered entirely online.

I was invited to conduct three separate teacher inquiries. For this first iteration of the cycle, I am interested in curiosity. Essentially, my question boils down to: …

…how can I provoke the curiosity of learners in my classroom?

If students enter and are curious about the world, then I reckon half of my work is over. If students are not curious, then it’s an uphill battle trying to do any teaching. Below is an adapted version of the presentation that I gave to other colleagues participating in the TLIF project and summarizes my understanding so far:

I find myself in Nottingham’s (2015) Learning Pit, in a process of “self-examination” (Foucault, 2001) trying to figure out the best way forward. My questions are threefold and surround firstly, the nature of eLearning itself; secondly, the underpinning philosophy of personalisation; and thirdly, the expectations on my personal well-being. Taking each in turn, I examine these questions below.

1. The problems with eLearning

The problem I find in my classroom setting with eLearning is that while this is an excellent tool, my experience rings true of the inequality of access to eLearning experiences as identified by Warschauer and Matuchniak (2010). As described in the TLIF proposal:

“In analysing evidence of equity, access and use of technology, Warschauer and Matuchniak (2010, in Biancarosa and Griffiths, 2012) found that high-achieving students were more likely to use technology for interest-driven activities such as researching topics or collaborating online to create new media, and they were more likely to have adult guidance in its use. They also found that lower-achieving students were more likely to use digital media for socially-driven activities such as chatting and playing games using social media. This led Biancarosa and Griffiths to question if the differences in the way students use technology may not only do little to shrink the knowledge gaps, but may in fact exacerbate them.”

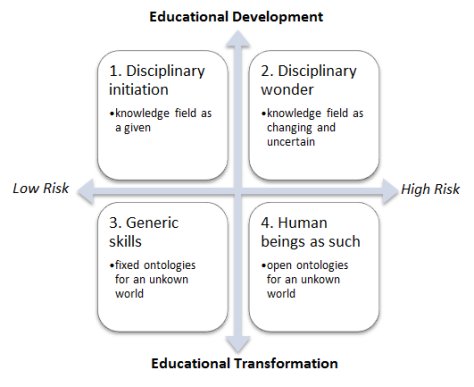

2. The underpinning philosophy of personalisation

Personalisation has a great many components and a strong theoretical basis for tailoring learning and educational approaches to the individual. Gone are the mass-produced models of learning, the challenge for teachers today is to provide personalised approaches to the learning environment. As Mark Treadwell argues in “The Conceptual Age and the Revolution,”

…Education has reached a critical point at which it is unable to improve performance without a paradigm shift (Treadwell 2008). He asserts that no matter how much money we put into the system or how much effort we make to improve it, there is no possibility of any ‘substantive increase in performance’. Treadwell compares education to other ‘technologies’ and points out that as a technology reaches its upper limit of efficiency, new technologies based on innovation rather than ‘an iteration of present technology’ emerges. Thus, for example, the technology of flight transitioned from ballooning to gliding, to powered flight, to jet engine, to scram-jets. In contrast, schools have moved ‘backwards’ to basic skills and standardised tests rather than leaping into a new paradigm. Treadwell argues that if we are going to substantially improve education then ‘doing nothing is simply not a choice unless (we) wish to deliberately empower learners with a dysfunctional set of competencies, skills, knowledge and belief about learning which are now almost totally irrelevant in the 21st century’.

The problem with this approach lies with the underpinning neo-liberal assumptions. That teaching and learning is a process that can be maximised for its outcomes is highly problematic. I find myself in disagreement with the many assumptions enclosed within this philosophy, trying to maximise learning, at the expense of the well-being of those involved in the learning process seems to kill off any sense of curiosity and wonder.

3. Expectations on personal well-being

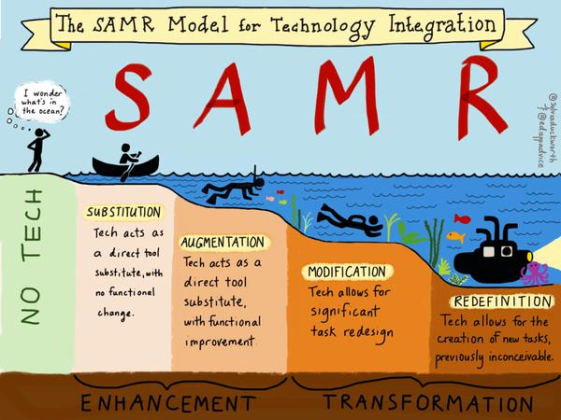

Hunkered down, I’m seriously questioning Tanim’s (2011) assertion that technology boosts learning by 12%. How does this work? Is a 12% gain measurable? In what type of classroom is this technology used and what does this look like? Examining Puentedura’s SAMR (2012) model, is this 12% at the Substitution, Augmentation, Modification or Redefinition stage? Many questions arise at this stage regarding this improvement that is identified.

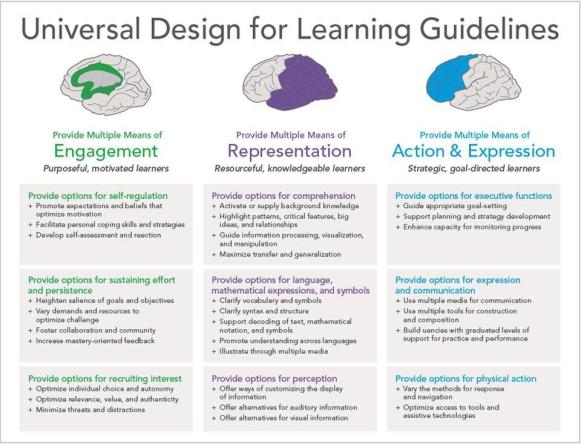

Clarity comes from the UDL Guidelines (CAST), an approach already employed by the Ministry of Education and CORE education, of which I attended a session.

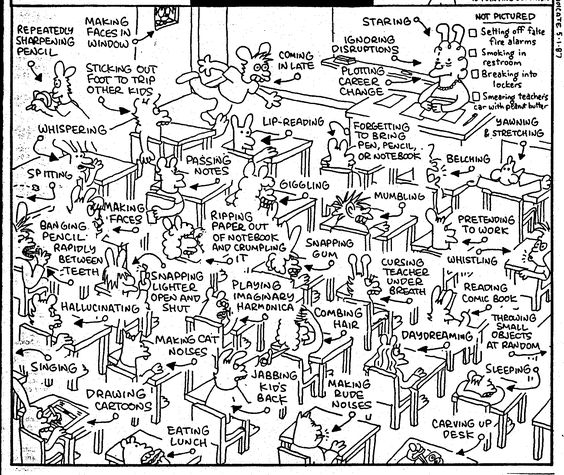

All of these UDL Guidelines are aspirational but overwhelming to be honest, requiring new training and an enormous amount of effort from staff to learn these new approaches. How do I sustainably teach in such an environment? Who will support me? How will I effectively teach in my classroom with all these best practices competing for attention, meanwhile Matt Groening’s depiction of the classroom is happening everyday I walk into the classroom. Have you ever experienced this situation in a classroom?!

My Teacher Led Inquiry

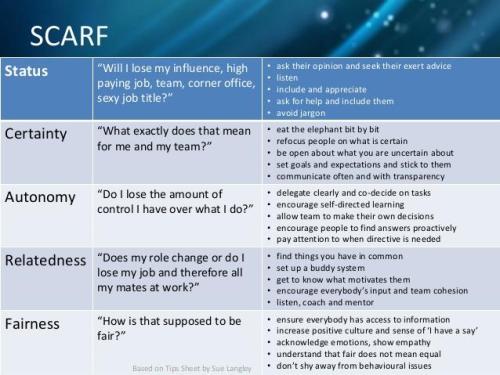

Nottingham’s Learning Pit gives significant opportunity for self-reflection. I find myself employing David Rock’s (2008) SCARF model to work through the anxiety that I currently find myself in. Rock’s SCARF model refers to aspects of Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness. I feel high levels of anxiety currently as I approach this “brave new world” of eLearning at the bottom of Nottingham’s learning pit. The many and varied questions I have are majorly based around the premises of the project with its assumptions surrounding eLearning and personalisation discussed above.

Examining the barriers and facilitators to these two intertwining ideas, provides some navigation through the situation. The barriers I can identify are threefold and include: firstly, social media and the distraction from learning are real and hugely problematic for lower achieving students in my care. Secondly the “fad” of the latest shiny toy distract from deep learning is evident throughout learning as we engage students in surface level learning to keep “engagement” high but lacking real substance. Finally, Puentedura’s (2012) SAMR analysis reveals that much of eLearning is merely just substitution, and in my own pedagogical frame of reference, I find that this is enormously true still. In contrast to this idea, however, my mentor for this TLIF project says about the SAMR model:

“It might pay to also look at some of the critiques of SAMR, such as this one here. Sometimes I wonder if SAMR puts too much emphasis on the technology, rather than the learning. For this reason, I prefer the eLearning Planning Framework (and just focusing on the Teaching and Learning strand in this context), and sometimes TPACK.”

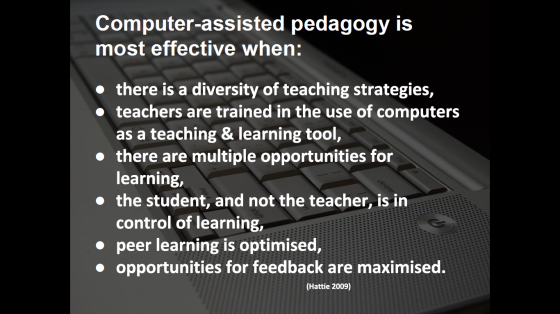

Against these barriers, are a number of facilitators, including Hattie’s (2009) analysis of computer-assisted instruction (or pedagogy as Osborne labels it in the slide below); UDL and literacy strategies.

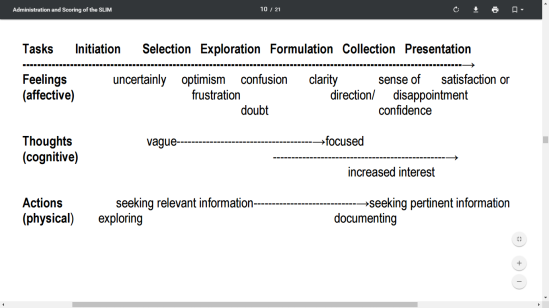

Despite my many reservations therefore, I am reminded of Kuhlthau’s ISP model (below), pertinent to this discussion and significant at driving the necessary curiosity proposed by Callison’s inquiry cycle (next page).

Hattie’s (2009, p. 220) findings on the diversity of teaching strategies rings true for me moreso, and I’m wanting to explore this further in my context. One student voice from my 2016 teacher inquiry indicated that more project-based social inquiry with reduced screen-time gave the ability for “freedom of what I wanted to study and learn”. I appreciate Cardno, Bassett and Wood’s (2016) guidance therefore in this process on being: “open-minded, fallible and persistent.”

The key to success? Duckworth’s “Grit” ( 2014).

I am interested therefore in the process of the social inquiry model and would like to explore how a diversity of eLearning teaching strategies can lead to transformative learning (with deep engagement) at Puentedura’s (2012) M/R depth of understanding, piquing curiosity and this deep learning in students to optimize peer learning and maximise feedback.